August 9, Sacramento, California—I’m at Roots Coffee at 5th and J Street. I remember getting on the train in Klamath Falls with my backpack all in one piece—no frantically emptying water bottles into the garbage can, no digging desperately for laptop and phone and placing them in their own gray plastic bin, no removing my shoes, belt, and button-down shirt and stepping into a glass cylinder with my hands up like I’m facing down a cop with a gun. I just walked from the station to the platform and jumped on board, pocketknife, pepper spray, full-size toothpaste and all. I stuffed my huge backpack onto a shelf and climbed the stairs to my wide seat with its extendable footrest, leaned my chair back all the way—without crushing the knees of the passenger behind me—and stared into the blackness out my huge picture window while the gentle rocking rumble of the train lulled me into a profound calm.

I’m not saying coach is comfortable. No matter how I arrange my body, the gaps between my back and the seat prevent the natural alignment of my spine, and regardless of how I contort my limbs, an arm or a leg goes numb every hour or so. But my seat is so broad that, when necessary, I can toss and turn without waking my seatmate. I can also get up and wander the length of the train at will to encourage blood flow. All of this makes riding coach in Amtrak far superior to riding coach in a plane.

Also, they let you off the train for fresh air when you’re delayed indefinitely. Unlike Delta Airlines, which leaves its guests sealed into a metal capsule on simmering asphalt when it’s 111℉, refusing to turn on the air conditioning or to let them deboard until they’re suffering from heat stroke and must be removed on gurneys. I despise the aviation industry. In fact, I have a rule: Unless someone I care about is dying, I’m not flying.

I already hate my backpack. I love it the way a turtle loves its shell, but I hate it too. I could go anywhere, and I would be at home, but although I tried extra hard to minimize, it’s still too huge, too heavy, too awkward and bulky. It is monstrous. I won’t be happy until I can survive with nothing but a hatchet.

I checked my backpack in Sacramento so I wouldn’t have to carry it around for six hours. It’s a luxury to be able to ditch that monster at a ticket counter and spend my layover meandering about, drinking $4 coffees in hip cafés. It’s a luxury I didn’t have the last time I traveled alone. That was about fifteen years ago. I had no money then—unless I wanted to crawl out of my tent before dawn and walk a few miles to the nearest temp agency and sit on old, hard, dirty carpet for hours, drinking old, stale coffee out of a Styrofoam cup, hoping for a day gig digging holes on a construction site or sorting clothes in the back room of a thrift store… or unless the person who’d picked me up hitchhiking realized I was penniless and insisted on giving me a $20… or unless I’d just finished a seasonal job cleaning guest cabins at some expensive resort in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho… The point is, money was not something I reliably had, so I couldn’t afford trains or $4 coffees, and I certainly couldn’t pay someone else to babysit my monstrous turtle shell all day.

Roots Coffee is on the fringe of what Sacramento calls the Downtown Commons. It’s a giant mall—a wide pedestrian pathway flanked on either side by expensive shops and a palatial movie theater. In the center, big brightly colored block letters spell out DOCO. The D and the O are stacked on top of the C and the other O so that they form a nice square. This annoys me. I can’t even say why. That kind of deliberately hip abbreviation makes my collarbones turn to cockroaches and skitter down into my stomach. A neighborhood should have to earn an abbreviation like that. I don’t know how old this mall is, but it looks brand new. It’s spic and span. Clean shops with clean tables and chairs all along the wide walkway. The public bathroom is unlocked, and even that is sparkling clean. Women in wide-brimmed straw hats and ruffly sundresses stroll past Punch Bowl Social and Feho & Rig. I don’t know what any of that means, but I guess they do.

Security guards stride purposefully among the serenely strolling shoppers. They are many, which explains the total absence of houseless people… which explains the empty lounge chairs and the cleanliness of the unlocked public bathroom. Janitors push yellow mop buckets and carts laden with garbage bags and cleaning solutions. One wields a long stick with what looks like an ice scraper on the end. He uses it to peel black gum off the pavement. What neighborhood does he live in? Does it have a hip acronym spelled out in colorful block letters? Does scraping gum off the pavement pay him enough to buy anything from any of these shops? Would an hour pushing that grimy yellow mop bucket buy him a popcorn at that palatial movie theater?

I walk all the way through DOCO. When the security guards and janitors fade out, the houseless people fade in. One man sleeps on the concrete in a doorway, another slouches in a wheelchair with bulky shopping bags hanging off the back, and a third shouts aggressively, waving his arms as he flails into traffic. A woman stands in front of a boarded-up Chinese buffet, eating food out of plastic containers that rest on a metal railing. A few dirty shopping bags rest at her feet. She looks up as I pass, the ruffle of her pink bonnet framing a smiling face.

“How are you this norming?” she says.

“I’m doing pretty good,” I say. “How ‘bout you?”

“If I were to complain, I’d be foolish,” she says.

She’s eating standing up, out on the sidewalk, in a neighborhood that smells like piss, and she can’t complain. I wonder where the women with the straw hats and ruffly sundresses are eating. I wonder if they’re complaining.

Since I have six hours before my next train leaves, I wanted to get a haircut, but the first place I called that was within walking distance quoted me $85. No. Just no. Not when I know that in any neighborhood outside DOCO I could probably get one for $30.

The problem with downtowns in the United States—especially on the west coast—is that if you don’t want to buy expensive shit, there’s nothing to do. If this were Querétaro, Mexico, an experimental theater group would likely be performing aerial acrobatics in the plaza for free. If it were Chile or Argentina, a dance troupe might be demonstrating the tango or the salsa. There would be a cart selling cheap strawberry tamales, or a random person sitting on the sidewalk, selling homemade empanadas out of a cooler. And you could probably buy the whole cooler for the price of a small popcorn at the DOCO movie theater.

Don’t worry, I am leaving. I’m on my way to Florida to take a boat going to Spain, where I’ll walk the Camino de Santiago. Form there, I’ll make my way to Ireland, where I’ll walk the Ireland Way. After that… I don’t know. I’ll be back eventually. I’m not one of those people who thinks Europe or Latin America or any other place is better than the US. I’m definitely not one of those people who thinks the US is better than every other country in the world. Every place is fucked in some way. No country in the world is immune to corruption. Everywhere you go, someone will try to take advantage of you somehow. All I’m saying is there are things I like about the US—like national parks you can hide in for weeks at a time for free—and things I despise, like consumer culture.

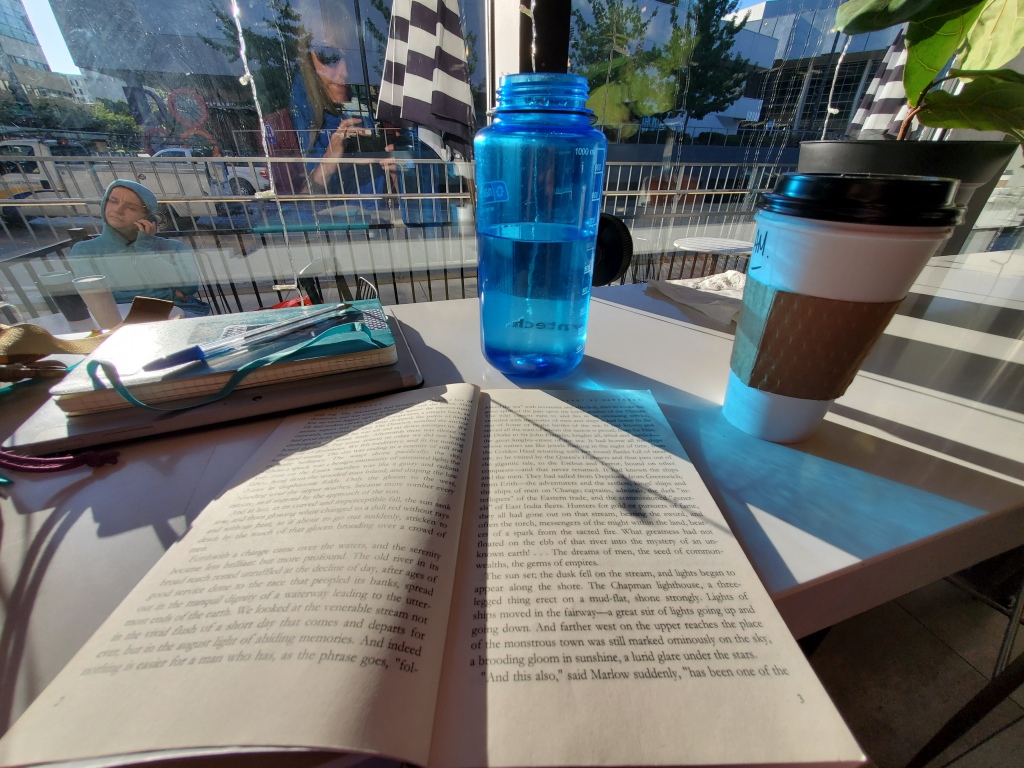

August 10, Salt Lake City, Utah—A white sun beams from the blue peaks of the mountains like a crown jewel, lighting up the observation car, where I sit in a booth, drinking coffee and reading Heart of Darkness. School buses, semi-trucks and pickups hauling backhoes zip along the highway that hems in the feet of the mountains. Commuters zip to school, to the office, to the construction zone. Later, they’ll zip home. A zipper only goes two ways. Once you’re on it, you know exactly what you’ll be doing every day for a long while—perhaps the rest of your life. I know what I’m doing up until September 5th, the day I board my boat from Ft. Lauderdale to Barcelona. The second I disembark, my zipper unravels. The teeth fall out and scatter like sparkles across an ocean, leaving me adrift.

Anything could happen.

The zipper that holds Salt Lake City together zooms past vast parking lots. I suddenly realize that parking lots are a major factor in the revulsion I feel toward American cities. There are no words for the monstrous tedium of hauling a heavy backpack across a sweltering expanse of flat asphalt because you can’t afford a city bus out of town. I think I’d rather be stranded in Death Valley than in a parking lot on the edge of Salt Lake City.

“Next smoke break will be in Grand Junction,” the conductor says. “That’s about four hours from now.”

That’s gotta be rough. I don’t want to be addicted to anything. Not cigarettes, alcohol, coffee, mattresses, air-conditioning, running water, convenience, efficiency, or even underwear. I don’t want to be stuck on some old bus, bouncing in and out of potholes at three miles per hour on a cliffside dirt road that’s about to crumble into a canyon with my teeth chattering and my bones all in a twist because I can’t get what I’m addicted to… or what I’m accustomed to. I want to be able to adapt. Calmly. I want to be able to focus on the expert touch of the bus driver’s fingers as he tunes the radio, makes yerba mate, ties his shoe, and pilots the bus within a centimeter of certain death.

I had a lot of routines before I left Klamath Falls, but travel works on routines the way the friction of constant wear works on a sweater. The fibers fray and fall away one by one until there’s no form or structure. After a while, I wonder why I thought I needed a cup of coffee every morning. After a while, making sure I stop eating at 7:30 and start again exactly sixteen hours later so I can get a long enough fast to induce the production of human growth hormone seems utterly absurd. Travel works on the brainwashing effect of a trip down the YouTube “wellness” rabbit hole the way a sledgehammer works on a Starbucks window. After a while, all the disordered eating behaviors I never would’ve admitted were a problem shatter like glass and I can just eat when I’m fucking hungry instead of trying to be perfect.

I can unravel like the long mournful bellow of a train whistle. That’s a sound that always called to me. When I hear it, I picture freight trains, not Amtrak. If you can count the lugnuts, it’s going slow enough to jump on. That’s what I’ve heard anyway. I picture trying to jump back off and getting my hair caught in the wheels. I really do want to cut it off. I’ve been considering shaving my head for years. One thing I really don’t want to be addicted to is the idea that my value lies in my looks. There are multitudes of magazine articles that tell women how to be sexy at 40, at 50, even at 60… Fuck. How exhausting. When do I get to stop trying to be sexy? When do I get to forget about the eyeballs of men and reclaim the half of my brain that my patriarchal culture insists I dedicate to the futile pursuit of perpetually youthful physical attractiveness?

Now. I’m doing that now.

Or whenever I can find someone willing to cut my hair off for less than $85.

In the afternoon, when the observation car fills up with people and noise, I retreat to the downstairs café car. It’s darker and quieter and the attendant is friendly. At another booth a young man sews a vest with a needle and thread. I think of all the hours I’ve spent sitting in tents or in public libraries sewing the side-seems of thrift store t-shirts. The young man reminds me of all the road kids and activists I’ve known. He has big curly hair and glasses, wears a bandana around his neck and a bracelet made of bicycle chain on his wrist. I wonder what his story is, but I’ve been terrified of people lately.

If you want to talk to someone, all you have to do is look at them and smile, I tell myself. It’s not that fucking hard.

I try it and he asks if he can join me.

B is not a road kid, but he is an activist. He’s fascinating and extremely intelligent. He lives in the northwest and he’s on his way to a wedding in the midwest. He went to college for engineering. When he told his professor he was considering getting a PhD, the professor told him he would end up working for a big corporation and that he’d hate it because he’s too much of an idealist. His other college pursuits included joining a sort of Cirque du Soliel group where he learned to juggle and ride a unicycle. He loves regular bicycles too. He’s involved in a mutual aid group where he serves as a bicycle mechanic. Mutual aid, communism and anarchy seem to form the core of B’s personal value system. He lived on a commune for about a month once, and he doesn’t just read Marx and Lenin; he actually retains the ideas and can recall and discuss them in detail, which is more than I can say for myself. B also started a poetry reading and a poetry zine called “Raising our Voices,” and he plays guitar, piano and trumpet. He wants to start a printing press and an alternative news outlet focused on informing the public about the insidious actions of the police. His friends think he lives a wild life, but he insists he has the mind of turtle, that he spends lots of time thinking about things before doing them. However, he does occasionally take off on a spontaneous three-day bicycle camping trip. B and I talk for a few hours, and before he gets up, he gives me his number so I can track him down whenever I return to the northwest.

August 11, Hastings, Nebraska—I’ve learned to sleep curled in a little ball between the hard plastic and metal of two armrests, with nothing but a light cotton scarf for a blanket. I’ve also learned that I should wear sandals on long train journeys and refrain from checking my backpack. I’ve been wearing shoes—over the same pair of socks—for three straight days, even while sleeping. These are my hiking shoes, which means they’re well-seasoned with sweat, which means that after my six-hour walk around Sacramento, taking them off would release an unpleasant odor. I don’t wanna be that guy. But I do feel like my feet are encased in suffocating cement blocks, and the ball of my right foot feels sticky. I can’t wash my foot and change my socks because my fresh ones are in my backpack, which I checked so I could walk Sacramento unburdened. My sandals are in the backpack too. Train travel is just like hitchhiking—it’s best to keep all your stuff with you at all times.

“Speak to an agent!” a fellow passenger says, enunciating loudly into her phone.

I’m sitting in the observation car, watching the sun rise and roll over the dewy green slopes of Nebraska farm fields.

“Refund!” the woman shouts.

I was asleep, so I don’t know exactly what happened, but our train sat immobile in Denver for about five hours last night. I’ll miss my connection from Chicago to Carbondale. That’s okay with me because I have several days before I have to catch the connection after that, from Carbondale to Indianapolis. Free time is a luxury, a privilege many people do not enjoy. I remember when I had no money. Sometimes, when I woke before dawn and sat waiting at a temp agency, no work ever came, so I got in line at the back of the local church and waited for a sack lunch instead, or I picked grapefruits off trees in front of apartment buildings, or I dumpster dove for donuts. Waiting at temp agencies and in sack lunch lines consumes a lot of time. So does having a real job. I remember the utter dread I felt every night and every morning when I worked as a mail carrier for USPS in Fairbanks, Alaska. I had to get up at four-thirty in the morning to make it to work. All I wanted then—all I want now—is for my time to belong to me.

“Speak to an agent!” the woman shouts.

I’ll deal with my own travel arrangements later. I have money saved up. I can travel for a bit before I start working. And I like the work I hope to be doing, so when I start doing it, I’ll feel like I’m living my life instead of spending my time.

“What is your employee ID number, ma’am?” the woman demands. “And all your calls are recorded?”

We’ve stopped in Hastings, Nebraska. I love the train because I get to see the backs of little towns. It’s like going backstage at a theater. Wooden stairways climbing brick buildings, stacks of pallets piled haphazardly outside the gaping garage doors of loading docks, backyards full of rusted cars, all with rounded counters reminiscent of the 1950s.

Because of the delay, hot beverages are free all day in the café car. I should ask the café car attendant his name. He likes avocados, has about six in his luggage. He could eat the $45 dinners the guests eat, but he prefers to bring his own food. “Better not to have all those additives,” he says. He’s worked for Amtrak for 17 years—six days on, five days off. He’s been divorced a while and his kids are grown, so it’s his dog he misses when he’s away.

“I used to have a schedule kind of like that when I drove luggage trucks for Princess Cruises up in Alaska,” I said.

“You lived in Alaska?” he says, his eyes brightening about a thousand watts. “Why would you give that up?”

“It was a seasonal job. Unfortunately, I had to go find other things to do once it ended.”

“Alaska is beautiful! I mean, I’ve never been, but I would love to go.”

A lot of people say this, but I think he actually might go, once he retires. His voice is pure awe and his blue eyes sparkle like glaciers.

I sit in the café car for a few hours with B again today. He sews the neckline of his vest while we talk. His stitches lie flush together like embroidery. B remembers everything he reads, not just about communism and anarchy, but about Mormonism and Catholicism and everything else. I feel like kind of a dufus trying to discuss these subjects with him. I envy people who can quote the texts they’ve read and then critically analyze them in conversation. I can do this with concepts like narcissistic personality disorder, intermittent reinforcement and psychological abuse. I can tell you how social media algorithms separate people into tribal echo chambers. I know what Mean World Syndrome is. I know stuff, I guess. It’s just different stuff. I have to get over the idea that I should know everything.

“How do you get people from opposite sides in the same room, talking face to face, when internet algorithms are showing them completely different search results?” I ask. “I mean, say I search the word anarchy. Because of my Google search history, I get results about utopian communes based on horizontal democracy and mutual aid. But say an alt-right Trump supporter from Klamath Falls searches the word anarchy. Because of their Google search history, they get results about how buses full of Molotov cocktail-tossing Antifa dressed in black are about descend on their town and burn it down. That’s how the internet is designed to work. So even if you and I create this utopian anarchist commune and it works perfectly, and even if seeing it in action would change their minds, they would never even know it existed because they’d never hear about it. So how do you reach them?”

“Mutual aid,” B says. “You help them. There are plenty of people in the houseless community I work with whose ideologies are opposite to mine. They might not like Trans people, for example, but when that Trans person is fixing their bike, which is their only transportation, suddenly it doesn’t matter anymore that they’re Trans. They’re just a decent person providing a necessary service for free.”

Such a good answer, and so obvious now that he’s said it. You don’t go to Freemason meetings and People’s Rights meetings and invite people to events where they know they’ll be asked to sit across from a liberal and discuss contentious issues. There are groups that do this, like Braver Angels, and they’ve designed genius mediation structures that make for very productive, mind-changing conversations, but I’ve found it’s near impossible to get conservatives to come to such meetings. You don’t ask them to come to you, you go to them. You find out what they need and help them get it.

“So, say there was this utopian anarchist society, and it was running smoothly, and everything was beautiful and you lived in it,” B says. “What would you do then?”

I’m amazed to find that I don’t have to think about this.

“I’d do exactly what I’m doing now. I’d travel around and I’d write about it… What would you do?”

“I’d be farming,” B says. “I’d probably have some friends I’d play music with on a semi-regular basis. I’d also probably have like a little shed with parts and tools so people could come to me and be like, hey, this is broken, can you fix it?”

B gets off in Iowa. He’s there to attend the wedding of the first person he ever dated.

I eventually get off in Chicago. I’ve missed my connection to Carbondale as expected. Two others—a high school girl in a pink track suit and a retired man with a white ponytail and a Hawaiian shirt—have missed their connections to Minooka, Illinois. Amtrak provides vouchers for Swissôtel, a swanky place right downtown. They give us sandwiches from a local deli and forty dollars worth of food vouchers. We even get a shuttle ride to the hotel. But the shuttle won’t be available tomorrow.

“You’ll have to get a cab back to the station,” the agent explains. “Just make sure to get a receipt and bring it to the ticket counter tomorrow and you can get reimbursed.”

This seems weird to me. Check-out time at the hotel is eleven in the morning. Why wouldn’t the shuttle be running at that hour? Maybe she’s talking to the other two. Their trains leave much earlier than mine.

We follow the agent to the shuttle bus. When she steps onto the escalator, the girl in the pink track suit balks and blushes.

“I’m scared to go up escalators,” she says. “I love rollercoasters, and I can go down an escalator just fine, but I can’t go up.”

The agent reroutes us toward an elevator.

The girl is going to Minooka to see her boyfriend, who attends the university there. On the way to the elevator, she tells me how she met him.

“I was so shy. I saw him play in a basketball tournament and I thought he was so cute, so I found him on the team roster and added him on social media and we starting messaging and we’ve been in love ever since!”

Her eyeballs graze the ceiling as she swoons, then they land on her hotel voucher.

“Is this my train ticket?” she asks.

“No, that’s your hotel voucher,” I say. “Did you get an email from Amtrak? They should’ve sent you an updated train ticket. You can download it.”

She checks her email.

“Thank you so much!” she says. “I never travel! I’ve never left Iowa. I live in Burlington. It’s the most boring town in the country. We do not have a good reputation. We have the highest crime rate in our little area.”

“I’m from Tucson,” Hawaiian shirt guy says.

“Oh, really? I lived in Catalina for a year,” I say.

“Where are these places?” the girl says.

“Arizona,” I say.

“You two have been to some cool places!” she says.

As we cross the road toward the waiting shuttle, I ask the agent, “So, there’s really no shuttle back to the station at eleven tomorrow morning?”

“No, you’ll need to get a cab and bring the receipt to the ticket counter to get reimbursed.”

The moment I enter my room at the Swissôtel, I remove my shoes. My feet are swollen. When I bend my toes, the skin feels like it’s about to crack open. I still don’t have my backpack, so I can’t change my socks or underwear. Instead, I wash the ones I’m wearing in the bathroom sink and use the hair dryer to dry them. I shower and lounge around in the complimentary robe, eating my deli sandwich and watching the news. It is such a relief to lie down flat, with my head against a soft pillow rather than a hard armrest, to sleep naked rather than constricted by waistbands and underwires and shoes like concrete bricks. The thing I’ve always loved about travel is, it makes me appreciate basic stuff like beds and showers and clean socks and underwear.

August 12, Chicago, Illinois—I muck about in my room naked for as long as I can, not looking forward to putting on underwear, socks and hiking shoes again. I drink both complimentary coffees. Why not? As instructed, I take a cab back to the station and ask the driver for a receipt. He writes one out by hand. As I’m walking away, I look at the total. It’s barely legible. I know it’s going to be a problem.

“Why didn’t you take the shuttle?” the Amtrak agent asks.

“I was specifically and clearly told—twice—that there would be no shuttle and that I should take a cab.”

He takes my receipt.

“We don’t take these hand-written ones. They have to be printed out.”

“Nobody told me that last night. I never take cabs. I wouldn’t have known to ask for a certain type of receipt.”

He looks at it again, sighs, calls a manager.

“Do we take these hand-written receipts?”

No. They do not.

He squints at the total, calls another agent over.

“Can you read this total?”

“No.”

“It says twenty dollars,” I say.

They ignore me, scrutinizing the receipt as if it’s written in Aramaic.

“It says twenty dollars,” I repeat.

“It has to be legible ma’am,” the woman says.

Really? You have to be able to read it? Well fuck me, I thought you were gonna eat it and shit it into a petri dish and analyze it underneath a microscope! I just barely manage to suppress a sudden fierce desire to punch her hard enough to crush her swollen condescension gland.

“Here’s a customer service number you can call to make a claim,” the man says.

This is how companies make money. They take twenty dollars here and twenty dollars there and they tell you to call customer service and make a claim—a process so complicated and time-consuming it doesn’t seem worth the amount they stole from you. What are they gonna do, mail me a check for twenty dollars? Where exactly will they send it? Probably not to the country I’ll be in when I need it. Bastards.

I try to remain calm.

“It’s as if I paid twenty dollars for a really nice hotel,” I mutter cheerfully as I leave the counter.

“No, it’s not,” my brain growls. “It’s as if you’ve been ripped off. It’s Amtrak’s fault you needed a hotel and a cab in the first place. There were times in your life when that twenty would’ve been literally all you had! Think of all the Amtrak customers who can’t afford to be ripped off for twenty dollars here and twenty dollars there!”

“God, I’m so not in the mood to stage some kind of elaborate protest over this.”

“And that’s why shit sucks. One stupid little jab after another and people just let each one slide because it’s never worth staging a protest over, and suddenly it’s 111℉ outside and you’re dying of heat stroke in a locked train car with no air conditioning because Amtrak doesn’t want to prolong a delay by deboarding and reboarding the passengers. Delays cost money afterall…”

“Thank you. Shut up.”

It’s only eleven-thirty. My train leaves at eight tonight. I walk the city.

Chicago is huge. The city sprawls vastly in all directions, but that’s not what I mean. I mean every building I look at crowds my brain with words like monolithic and colossal until my skull is so stuffed with concrete and glass it cracks down the center. Downtown Chicago forces you to look up in awe, but not the kind of awe with which you might gaze up at Mt. Denali in Alaska. Chicago and Denali are both so incomprehensibly massive they shrink you to the size of a germ. But Denali’s hugeness is compelling and enchanting. It beckons you with mystery and wonder. Chicago’s hugeness is imposing and exclusive. Its hard glassy sheen says, “You will never be privy to what goes on behind this glare.” Denali’s unfathomable size creates a tantalizing distance. It is alluring but elusive and it is completely indifferent to you. Chicago is more like a bully. It towers over you, demanding your attention and saying, “Admire me or I will crush you.”

Chicago gives me the fear.

I walk until I come to a fountain. Two rectangular towers of glass bricks stand opposite each other on a smooth concrete floor. Sheets of water spill from each tower and spread to cover the ground. Adults take selfies in front of the waterfalls while their kids wallow and splash. A girl lies down in the shallow water, pinches her nose closed and rolls like a hot dog, her long black hair whipping water around like a garden sprinkler. A bow-legged baby in a striped onesie dangles from his mother’s hand, slipping and sliding until he falls splat on his butt. Climbing to his feet again, he staggers into a curtain of water, arms outstretched, and stands stunned with amazement. A young woman wearing thigh-high black tights, combat boots and a Tank Girl haircut strides by like a Vogue model, an entourage of two pudgy, dumpy men in tow. When she leaps lithely cross the water, they galumph awkwardly after her.

The towering columns and glassy facades of Chicago don’t pique my curiosity like the understructure of the L or the layers of stickers plastered onto the backs of street signs. They don’t make me smile like the young man in the reflective vest blowing bubbles outside the Zumies shop. They don’t blend into my soul the way the jazz sax on one block fades into the blues guitar on the next block, the notes of two buskers barely touching like the fingertips of God and Adam in Michaelangelo’s Sistine fresco. The glass and stone can’t touch the sad perseverance of the brother and sister sitting on the sidewalk in front of Circle K, selling Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups—or their mother, who sits on a corner a block away, doing the same thing. They can’t love like the young man who puts an arm protectively around his boyfriend’s waist as they step into a crosswalk, or the young girl who rests her head on her boyfriend’s shoulder. They’re deaf to the desperate rage of the woman in the wheelchair screaming at passersby over the tattered edge of her cardboard sign.

I can’t claim to know Chicago. I only know what my five senses can tell me. I know how it makes me feel. Downtown Chicago’s colossal exclusivity isn’t made for music, love, sadness, desperation or curiosity. It’s made for money.

Maybe if I still had that twenty bucks in my pocket, I could buy my way in.

Well, I’m going to have to live a bit of life through your eyes. My turtle shell is on a storage shelf filled with gear and none of that is coming off the shelf any time soon. And my zipper won’t be unraveling soon either, although there maybe is a partially unraveled zipper happening? It’s my turn to go hang with my mother for a few months. Her schedule is very flexible and she doesn’t need constant attention, so I’m going to unravel for a few hours every day and then reravel later.

LikeLike